Propellers, Cedar Street

Orange rocks, Ringo Street

Propellers, Cedar Street

Orange rocks, Ringo Street

The Lake Dick Cooperative was an experimental New Deal project to help establish struggling families – white families, it should be noted – on farms of their own around Lake Dick, an oxbow just across the Arkansas River from Pine Bluff. Families from 29 Arkansas counties were selected. The project, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, had "the twin goals of establishing a cooperative community of farmers, and assisting sharecroppers and tenant farmers to become independent landowners." It would function as a cooperative until near the end of World War II.

The Resettlement Administration, which had initiated the project in 1936, soon became part of the Farm Security Administration, and in the fall of 1938, the FSA sent photographers Russell Lee and Dorothea Lange to photograph the settlement, including the newly built houses that lined the lake. (There are more than a hundred photos from Lake Dick by Russell Lee and Dorothea Lange – everything from domestic life to cotton cultivation – at the FSA catalog on the LOC website.)

According to a National Register of Historic Places nomination form filed in 1975:

"[The Lake Dick Resettlement Project] consisted of 80 houses of four to six rooms each, six community buildings, three mule barns ... The houses and community buildings were of simple one-storey frame construction with very plain lines and no decorative features. ...

"Most of the community buildings have been removed; however, the school-gymnasium still remains. It is used for storage, as a repair shop, and also houses farm offices ... Of the three large mule barns, only the south barn remains. ...

"About three-fourths of the original houses have been moved away from Lake Dick. The remaining houses, about 30, are those closest to the community center complex. These have recently been covered with white aluminum siding and reroofed with red shingles."

Later, the historian preparing the form slips momentarily from facts and documentation into commentary: "The land which once served a socialistic farming cooperative is now owned and operated by a single farming concern. Employees of the large landowner now occupy the houses built for members of a profit-sharing farming enterprise."

And while there may have been about 30 houses remaining in 1975, when we visiting earlier this week, only four of the houses could be found, and one old mule barn south of the lake.

Left: Type of house, Lake Dick Project, 1938. Russell Lee.

Right: One of four remaining houses from the Lake Dick Project, 2018.

Left: Types of houses. Lake Dick Project, 1938. Russell Lee.

Right: Remaining houses, 2018. James Matthews

Another of the original houses has been added onto over the years – most noticeably, the extension on the right side – but the chimney and the rectangular roof vent above the front porch still make it easily recognizable.

A third house has been reconfigured. The front porch has been enclosed and the entrance moved to the side of the house, but the chimney placement and shape and the overall layout are the same.

Left: Kitchen in farm home, Lake Dick Project, 1938. Russell Lee.

Right: Bathroom in farmer's home, Lake Dick Project, 1938. Russell Lee.

Left: Panoramic view of Lake Dick Project, 1938. Russell Lee.

Right: Panoramic view near Lake Dick, 2018. James Matthews.

I was unwilling to climb any higher up the old water tower, but apparently Russell Lee was more fearless. His photo appears to have been taken from the top of the same water tower, which appears in the next photo.

Warehouse and water tower, 2018.

Left: Schoolchildren, Lake Dick Project, 1938. Russell Lee.

Right: Cotton pickers, day laborers, waiting to be paid at end of day's work, Lake Dick, 1938. Russell Lee.

In an interesting side note, the Lake Dick area seems to have been the birthplace of blues great Big Bill Broonzy, according to an oral history interview with music writer and researcher Bob Reisman. Reisman recounts speaking on the phone to Broonzy's mother "and, in fact, was able from that point forward to determine that Big Bill Broonzy in fact had been born not in 1893, but in 1903 and not in Scott, Mississippi but in Jefferson County, Arkansas about 65 miles southwest-- sorry, southeast of Little Rock near Lake Dick."

"I certainly don’t want to take ownership over anyone’s history nor do I think that quilt making or folk art needs my elevation. ... Quilters are very precise in their geometry, technique and symmetry and I am in awe of that skill. But I’m not invested in perfect lines and construction with this work... . I think if a legit quilter took a look at my handy work they would be horrified."

from in interview at Arte Fuse

Driving around looking for material this morning, I found an empty lot on South Main with a newly dug foundation. The clay looked promising so I got out to check, when a man in a truck stopped to ask what I was doing there. I find that the oddness of the truth – I'm here to check out the clay for sculptures, or I'm here to see if any new dogs have been dumped – sufficiently confounds most people. They usually cock their heads sideways but say nothing, and then just drive off.

After the man left, I formed a handful of the clay into various sized lumps and squeezed them together (though the shadows give it a slightly anthropomorphic look that was not intended) and set it atop some bricks, with the flooded foundation footings in the background. My original intent was to photograph it as part of my Refuse Sculpture series, but it seemed to me a new thing.

So now I am thinking: What would it look like to create a series of found-object and clay sculptures from a single lot? To make them and display them on the lot itself?

BLVR: You’re selling bottles of contaminated water from Flint, Michigan, as a fund-raiser. Besides raising money, what is your interest in distributing bottles of contaminated water?

PL: ... My interest in selling contaminated drinking water goes beyond Dadaist hoo-ha. Beyond the gesture. Or maybe Flint is ultimate Dada. ... Art-wise, the aesthetics in this work are in the immaterial: vulnerability, community, and a sense of connectedness. ...

BLVR: Do you see any problem with equating art and social activism? Have you found that the activist impulse competes with the art impulse?

PL: Art. Activism. Activism. Art. They aren’t the same, but maybe they should be. I mean, should art improve the quality of people’s lives in a meaningful way? Fuck yeah. Should activism blow our eyes, ears, and minds? Fuckity fuck yeah. So there’s no problem.

from The Believer

"My paintings are invitations to look somewhere else."

"... I changed the location of things that they see every day and didn't know they were worth looking at. And so then when they go outside, they can see, 'Oh, I can see that."

via SFMOMA

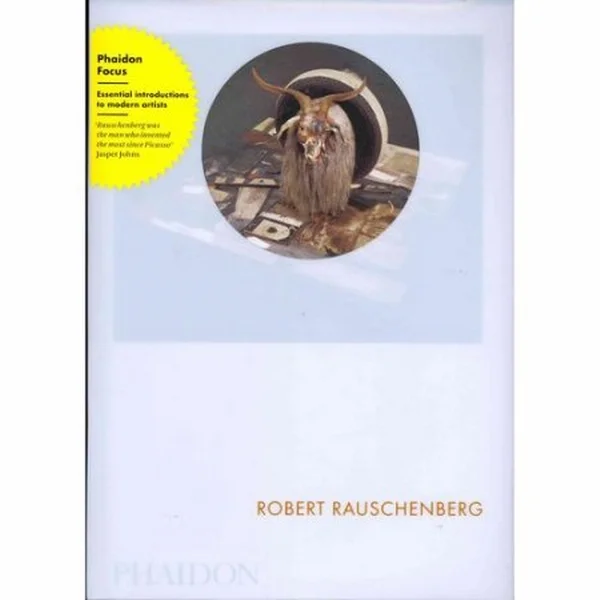

A Twombly next to a Keifer, in the same room with two Rauschenbergs, two Nevelsons, and a Basquiat. I was in in New Haven last week to visit a friend, and we spent a morning in the galleries at Yale.

Untitled, by Cy Twombly

Interior 2, by Robert Rauschenberg

Jack Johnson, by Raymond Saunders

Gift, by Lynda Benglis

Shield from Borneo

from Dawn's Wedding Feast, by Louise Nevelson

Ngbe Leopard Society Lodge Emblem, Nigeria

Plate, by Peter Voulkos

Diagram of the Ankle, by Jean-Michel Basquiat